Thinking like a Mountain. Thinking like a Mall.

Sculpture (2019).Four hundred puffin textile teddies. Variable dimensions.

Installation view.

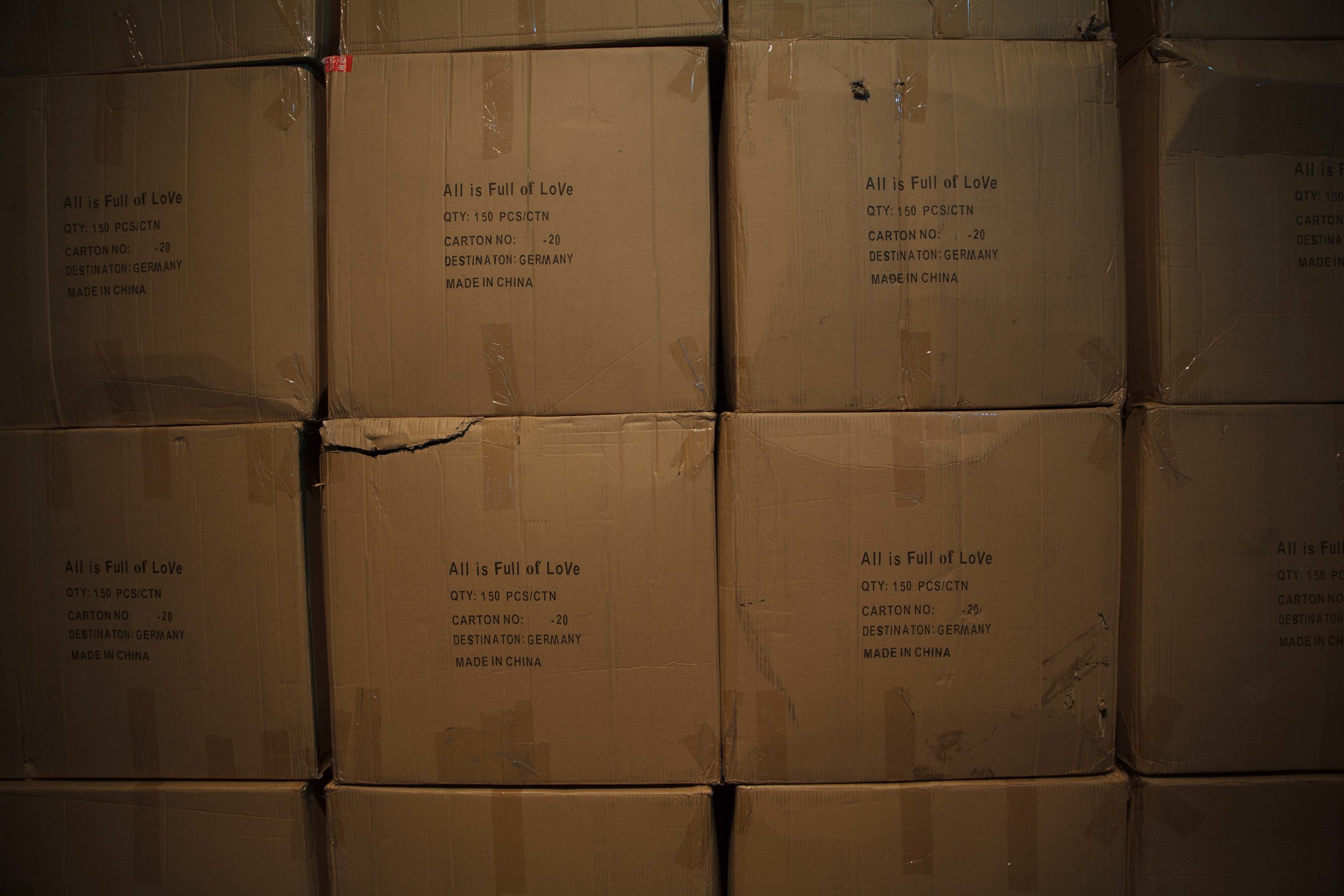

The Thinking as a Mountain sculpture originally appeared as part of a multi-media installation and artistic investigation All is Full of Love that was exhibited at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin in 2019. The sculpture is a direct reference to cult paintings by naive artist nicknamed Stórval (as of Kjarval) who often painted the same highland mountain, Herdubreid, that has a special shape of a table and has for its beauty been nicknamed ‘The Queen of Icelandic mountains’. The paintings are a popular collectors item in the homes of the culture elite of Reykjavik. The installation itself surveyed contemporary manifestations of crypto-colonial patterns in the artist home country Iceland by focusing on the obvious, massive growth of the tourist industry on the one hand, and the less visible but imperative fish industry on the other. These manifestations became a means of discussing gentrification processes taking place in Iceland in the years preceding the exhibition by utilizing a triangulation between fish, tourism and art.

Installaton view

All is Full of Love used as its building blocks various art works that had been created during the Keep Frozen artistic research project and the evolving figure of the-artist-as-a-puffin that had first appeared in 2006. Thus the installation investigated the role of colonial relations in identity formation and their conditional effects through recent, past and current predicaments. Connecting the three most important industries in Icelandic modern times the artist positioned herself as the evolving figure of the-artist-as-a-puffin while underlining the manual labour that prevails, in spite of shifting class structures.

It can shed some light on the figure of the artist as a puffin how the scholar Ann-Sofie Gremaud has claimed that “norientalist” stereotypes can be viewed as a process of European-colonial reciprocal identity formation. As Hegel has explained, identity processes rely heavily on mutual confirmation: The center needs to define a periphery (an “other”) in order to define itself. Iceland has certainly played a vital role as “the other place”, where explosive natural power has been juxtaposed to the long history of European culture. Historical colonial association with the natural state has for instance led to Icelanders being perceived as more original, authentic, unspoiled or even uncivilized and barbaric. Reactions to that perception have sometimes included its rejection, whilst at others, embraced it and so been complicit in self-exoticisation.

The exhibition commented on a post-bankruptcy Icelandic economy that came to rely heavily on the creative industries and entrepreneurial tourism. To cater for visitors, gentrification had been occurring at all levels of the community, not-least with so-called 'puffin shops' serving every Instagram-able tourist need while the harbour areas are being transformed into ‘authentic’ leisure centers ‘with a view’.

Issies and questions raised are not specific to Icelandic society but and instance linked to developments on a global scale due to the expansion and reach of capitalism and the neo-liberalization of the the principles of the welfare state. In this way, it is both the story of ‘an other’ and relatable to the wider context of socio-political and ecological unrest in the world today.

Installation view

Installation view