Keep Frozen at Berlinische Galerie, Berlin.

Keep Frozen

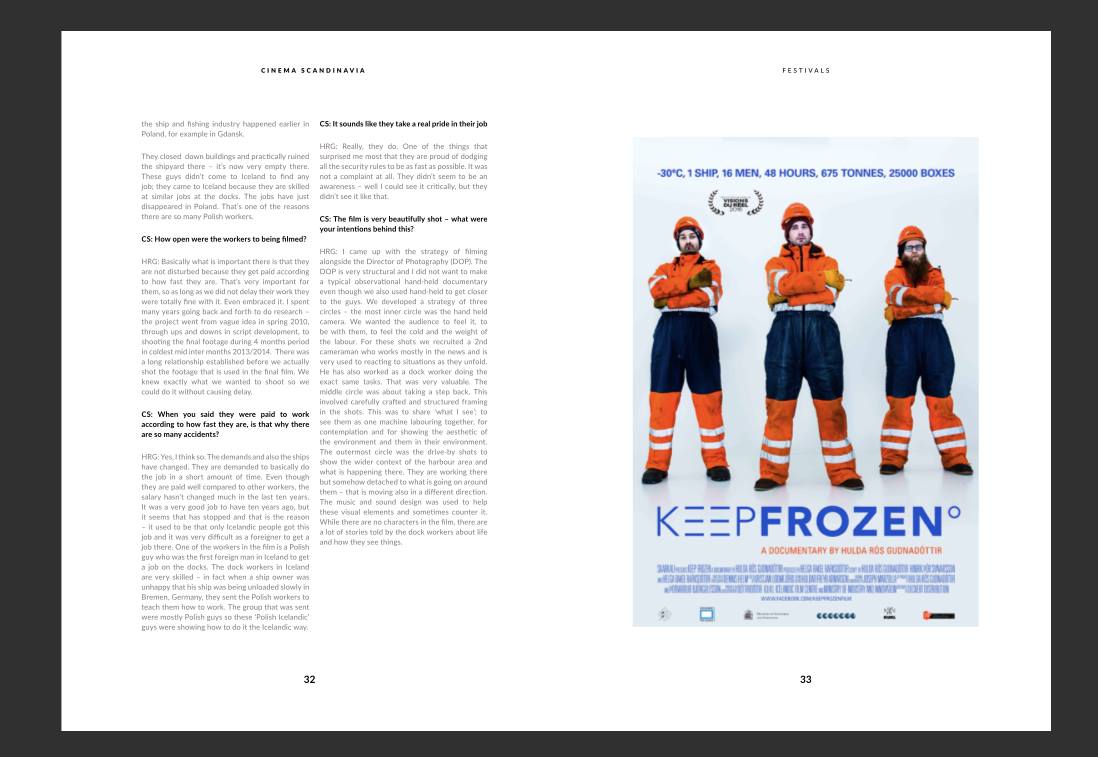

HD, documentary, 00:68:00, 16:9, 2016.“In the night and cold of the Icelandic winter, workers are organized around a trawler returning from deep-sea fishing whose holds are full of frozen fish. There are 20,000 crates of 25 kg to unload in 48 hours. The temperature in the fridge is -35°C and, on the quays, the snow crunches under big safety boots. The guys doing this work are tough. The slightest error, the slightest wrong move, could be an accident that costs them their lives.

In Keep Frozen they become virtuosos. The forklift trucks intersect as if in a dance, the crates seem incredibly light and float among the snowflakes. Here, the crude lamp lighting carves out the stage of a real ballet in which the setting, between the hangars of the docks and the fishing trawler, covered with a soft layer of snow, contrasts sharply with the harshness of the work. It is the sound that reminds us of their true status. In voice over, their stories, disembodied as never linked to a particular man, evoke their lives beyond this scene. At the same time, it is this treatment that transforms this group of men into a real team, which is united, and which gives the strength of achievement.”

Still frame from 'Keep Frozen'. DOP: Dennis Helm.

Read about the sister project Labour Move, a 3-channel video installation.

Still frame from 'Keep Frozen'. DOP: Dennis Helm.

World premier @ Visions du Reel 2016 in the 'Regard Neuf' competition.

Icelandic premier @ Bíó Paradís, art-house cinema, Reykjavik, May 2016.

Winner of Skjaldborg film festival, May 2016.

Nordic premier @ Nordisk Panorama 2016 in the best documentary competition.

Eastern European premier @ Warsaw Film Festival 2016 as part of best documentary competition.

German premier @ DOK Leipzig 2016 as part of International Programme. Nominated for EU - OSHA award..

Nomination for best documentary at 58. Nordic Film days in Lübeck, Germany.

Brotfabrik programmkino, Berlin.

Screening as part of Docu/Life section at Docudays UA in Kiyv, Ukraine.

Nomination for best documentary at Pêcheurs du Monde, Lorient, France.

Nomination for best documentary in the World´s Workers section at FF Millenium, Brussels, Belgium.

Nomination for best documentary in the CivilDOC section at CineDoc, Tbilisi, Georgia.

Kino am Raschplatz, Hannover, Germany.

SCALA programmkino, Lüneburg, Germany.

FSK programmkino, Oranienplatz, Berlin, Germany.

'Cryptopian States'. Curated by Jonatan Habib Engqvist, Gudny Gudmundsdottir and Sara Oldudottir at the residency of the Icelandic ambassador to Berlin as part of Cycle Music and Art Festival.

Berlinische Galerie, Berlin (Berlin Museum of Modern Art).

Curated by Anna Bitterwolf as part of 12x12 programm.

Studio Olafur Eliasson Kitchen at Marshall house Reykjavik, Iceland. Curator Christine Werner.

'Line of Light' at Serendipity Art Festival, Panaji, Goa, India. Curated by Serendipity Arts Foundation.

Credits

Director: Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir

Co-script writers: Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir, Helga Rakel Rafnsdóttir, Hinrik Þór Svavarsson

Photography: Dennis Helm

Sound: Huldar Freyr Arnarson

Editing: Kristján Lodmjörd

Original music score composed by: Joseph Marzolla

Executive producer: Helga Rakel Rafnsdóttir

Production company: Skarkali ehf.

Distributor: Deckert distribution and Nordlichter

Co-producers: Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir (dottirdottir) and Thorvardur Björgúlfsson (Kukl)

Assistant Director: Karolina Boguslawska

2nd Camera: Grímur Jón Sigurdsson

1st Assistant Camera: Baldvin Vernhardsson and Pétur Már Pétursson

2nd Assistant Camera: Carolina Salas

Sound Recordist: Bogi Reynisson

Boom Operator: Ari Rannveigarson

Data Manager: Carolina Salas

Rough Cut: Dalia Castel

Color Grading: Bjarki Gudjónsson

Catering: Helena Hansdóttir Aspelund

Interviews: Hulda Rós Gudnadóttir, Karolina Boguslawska

Translation: Karolina Boguslawska, Kasia Breustedt

Proofreading: Luci Dayhew, Neil McMahon

Post Production Facility: Trickshot

Sound Facility: Sound Park Posthouse

Credit song 'Gvendur á Eyrinni' composed by Rúnar Gunnarsson and Thorsteinn Eggertsson and originally performed by Dátar. Performed by Prins Póló.

Made with the support of Icelandic Film Center, Icelandic National Broadcasting Service (RUV), The Culture Board of Reykjavik, etc.

Still frame from 'Keep Frozen'. DOP: Dennis Helm.

Interview with Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir about the film printed in the May 2016 issue of Cinema Scandinavia

“Why did you want to make a documentary about harbour workers?

I noticed that in the western world that manual labour is invisible and hidden from sight of the middle class and mainstream media. People generally don’t notice that manual labour is happening all around them. It was very interesting to me when I was telling my twenty-year-old babysitter that I wanted to make this film and she responded to me by asking if workers still existed. It really seems that people don´t notice that everything around them has been moved from one place to the other by someone. I think the general thought is that the biggest revolution in the last thirty years is the internet but as artist, filmmaker and essayist Allan Sekula has expressed: the arrival of containers really revolutionised the way we live and made today´s consumer society possible. It’s not just like most products fly around in airplanes around the world. Mostly they are moved by ships and there has never been a point in history were more products have been moved around the world. All those products need to be unloaded and transported all around.

”

Still frame from 'Keep Frozen'. DOP: Dennis Helm.

“In the documentary it says that the harbour is slowly being overtaken by cafés and galleries. Is it just that they are trying to push the workers out?

In my work I look at things from a very personal perspective. Personal comments are of course comments on global trends at the same time. What is happening is not specific to Reykjavik harbour - it´s happening in many harbour towns in the world. These harbours are becoming trendy tourist destinations. Reykjavík, New York and many other cities grew into big towns or cities around harbour activities and development. In Reykjavik it happened rather recently - the 20th century actually - and New York just a bit earlier. In the last decades of the 20th century however - with the birth and the growth of the middle class - it´s been a tendency for the new class to want to turn away from their working class background they come from only one or two generations back or even within the same generation. This also happened in England. Thirty years ago 2/3 of English people defined themselves as working class but today 2/3 of England define themselves as middle class. In both those communities the middle class has tried to differentiate themselves from the working class by displaying different taste and preferences. The harbour really became something that was ignored, even to the extend that the city-folks have developed a blind spot to it and are not aware that it´s the biggest fishing harbour in Iceland. They look at it as something that is empty but it´s actually not. They don´t see the labour that´s going on there. What makes the gentrification of Reykjavik harbour unique is that is is not about takeover of empty spaces but the contrary - in fact the regulation changed so you didn´t need to have a business connected to the fishing industry to rent a space on the harbour. Consequently the rents got higher and the little guys had to move out. The harbour area had its own ‘ecosystem’ where small service companies and larger companies lived in proximity. Now the small guys have had to move away as they can´t afford the rent. What has moved into those spaces are those new cafés, restaurants and ice creams shops. The people in the city see their middle class tastes taking over the harbour. They see it as the harbour coming to life. I find it very interesting.”

Still frame from 'Keep Frozen'. DOP: Dennis Helm.

Installation view from ´In Line of Flight´ at Serendipity art festival, Goa, India in 2018.

Installation view from ´In Line of Flight´ at Serendipity art festival, Goa, India in 2018.

Installation view from ´In Line of Flight´ at Serendipity art festival, Goa, India in 2018.

“CS: Most of the workers are not from Iceland – is it just that Icelanders don´t want to do the dirty jobs?

HRG: That´s a very interesting point. What has happened in Iceland in the last two decades or so is that Icelandic people don´t want to do the working class jobs anymore so they have become part of the global migrant labour system. In Iceland most of the work – for example at this company half of the workers are Polish. The biggest immigration to Iceland has come from Poland. I actually went to Poland as part of this research – I went to places along the coast. I went to some of these places that these guys started working at because the breakdown of the ship and fishing industry happened earlier in Poland for example in Gdansk.

They closed down buildings and practically ruined the shipyard there – it´s now very empty there. These guys didn´t come to Iceland to find any job; they came to Iceland because they are skilled at similar jobs at the docks. The jobs have just disappeared in Poland. That´s one of the reasons there are so many Polish workers.”

“CS: How open were the workers to being filmed?

HRG: Basically what is important there is that they are not disturbed because they get paid according to how fast they are. That´s very important for them, so as long as we did not delay their work they were totally fine with it. Even embraced it. I spent many years going back and forth to do research – the project went from vague idea in spring 2010, through ups and downs in script development, to shooting the final footage during 4 months period in coldest mid winter months 2013/2014. There was a long relationship established before we actually shot the footage that is used in the final film. We knew exactly what we wanted to shoot so we could do it without causing delay.

CS: When you said they were paid to work according to how fast they are, is that why there are so many accidents?

HRG: Yes, I think so. The demands and also the ships have changed. They are demanded to basically do the job in a short amount of time. Even though they are paid well compared to other workers, the salary hasn´t changed much in the last ten years. It was a very good job to have ten years ago, but it seems that has stopped and that is the reason – it used to be that only Icelandic people got this job and it was very difficult as a foreigner to get a job there. One of the workers in the film is a Polish guy who was the first foreign man in Iceland to get a job on the docks. The dock workers in Iceland are very skilled – in fact when a ship owner was unhappy that his ship was being unloaded slowly in Bremen, Germany, they sent the Polish workers to teach them how to work. The group that was sent were mostly Polish guys so these ‘Polish Icelandic’ guys were showing how to do it the Icelandic way.”

“CS: It sounds like they take a real pride in their job.

HRG: Really, they do. One of the things that surprised me most that they are proud of dodging al the security rules to be as fast as possible. It was not a complaint at all. There didn´t seem to be an awareness – well I could see it critically, but they didn´t see it like that.

CS: The film is very beautifully shot – what were your intentions behind this?

HRG: I came up with the strategy of filming alongside the Director of Photography (DOP). The DOP is very structural and I did not want to make a typical observational hand-held documentary even though we also used hand-held to get closer to the guys. We developed a strategy of three circles – the most innter circle was the hand-held camera. We wanted the audience to feel it, to be with them, to feel the cold and the weight of the labour. For these shots we recruited a 2nd cameraman who works mostly in the news and is very used to reacting to situations as they unfold. He also worked as a dock worker doing the exact same tasks. That was very valuable. The middle circle was about taking a step back. This involved carefully crafted and structured framing in the shots. This was to share ‘what I see’; to see them as one machine labouring together, for contemplation and for showing the aesthetic of the environment and them in their environment. The outermost circle was the drive-by shots to show the wider context of the harbour area and what is happening there. They are working there but somehow detached to what is going on around them – that is movign also in a different direction. The music and sound design was used to help these visual elements and sometimes counter it. While there are no characters in the film, there are a lot of stories told by the dock workers about life and how they see things.”