All is Full of Love

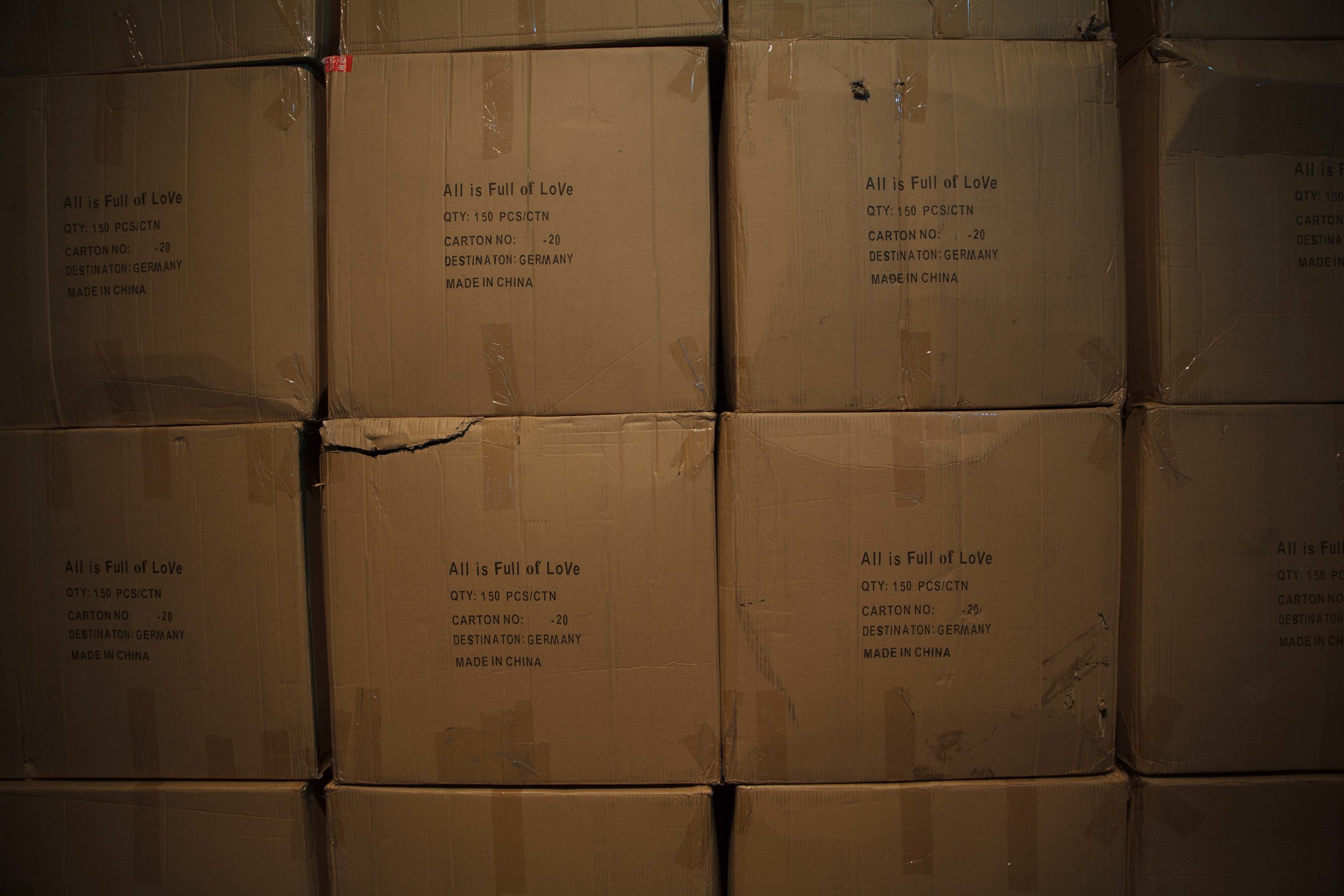

Mixed-media installation and solo exhibition at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin in January/February 2019The installation consisted of three triangle sculptures ‘Puffin Shop’ made of 2470 puffin teddies and 9 IKEA light wood shelves; original sound piece by Joseph Marzolla; ‘Artist as a Puffin’ digital C-print with archive ink on Hahnemühle Photo Rag Baryta 315 g. Sequence of fifteen prints, each H51 x W35 cm; ‘Thinking like a Mountain. Thinking like a Mall’ sculture made of 450 puffin teddies; 4 puffin hoodies; 3 channel synchronized room size video installation 'Labor Move'; 20 Keep Frozen export boxes; industrial grey metal strap machine; sculpture 'Golden ship', ca. 50x50x100 (irregular size) made of wireframe, gips, plaster, paper-mâché and 23.75 karat 'Rosenoble' gold leafs; HD16:9 video loop 'Material Puffin' on a 24 inch flat screen monitor with original sound piece by Guðný Guðmundsdóttir; 4 dockworkers working overalls with matching helmets; and20 'All is Full of Love' transportation boxes

Collaboration with Cycle Music and Art Festival (art director Guðný Guðmundsdóttir). Curated by Jonatan Habib Engqvist. Special thanks to the Icelandic choir in Berlin and its conductor Haraldur Þrastarson

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

All is Full of Love surveyed contemporary manifestations of crypto-colonial patterns by focusing on the obvious, massive growth of the tourist industry on the one hand, and the less visible but imperative fish industry on the other. These manifestations become a means of discussing gentrification processes currently taking place in Iceland utilizing a triangulation between fish, tourism and art. At the same time, they are tightly linked to developments on a global scale due to the expansion and reach of capitalism and the neo-liberalization of the the principles of the welfare state. In this way, it is both the story of ‘an other’ and relatable to the wider context of socio-political and ecological unrest in the world today (see longer text below).

Jonatan Habib Engqvist, curator

Installation view

Installation view 2nd floor

Installation view 2nd floor

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

Installation view

All is Full of Love was an artistic investigation and an installation project exhibited at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin that used as its building blocks not only new works but also various art works that had been created during the Keep Frozen artistic research project and even before that during the artist´s career. Thus it investigated the role of colonial relations in identity formation and their conditional effects through recent, past and current predicaments. Connecting the three most important industries in Icelandic modern times: fish, tourism and art the artist positioned herself as the evolving figure of the-artist-as-a-puffin while underlining the manual labour that prevails, in spite of shifting class structures.

2018 marked the centennial of Iceland's sovereignty, the seventy-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Iceland, the tenth anniversary of Iceland ́s near bankruptcy. 650 years of foreign rule – under Danish-Norwegian and sometimes Swedish shifting political structures – with Arctic agriculture as the main local activity resting on stringent labour bondage, formally relinquished. During this time the Danish king had maintained a monopoly in the valuable fish, whale oil and sulfur trade, and Iceland was one of Europe ́s poorest countries. Although Iceland did not have the status of being a colony of the Danish realm, the relationship with Denmark and other foreign powers continues to influence modern Icelandic development, both economically and culturally. The beginning of the 20th century marked a new freedom of the labour movement, along with the benefits of motorized fishing vessels under control of the newly freed Icelandic proletariat, paving the way for an individualistic ascent towards a better life. The economy of the newly independent state continued to be resource-based, dependent principally on fisheries. The end of the Second World War brought assistance from the Marshall Plan, and by 1974 Iceland was elevated from its status as a 'developing country'. Neo-liberal policies were adopted, incrementally and the 1980s were characterized by a number of privatization processes, including fisheries and banks, making them profitable for a class of local oligarchs. Within the course of a century, peasants had become the proletariat, who became the working class, who became the middle class, who then became a creative class. A post-bankruptcy Icelandic economy came to rely heavily on the creative industries and entrepreneurial tourism. To cater for visitors, gentrification is now occurring at all levels of the community, not-least with so-called 'puffin shops' serving every Instagram-able tourist need while the harbour areas are being transformed into ‘authentic’ leisure centers ‘with a view’. In 2018 Iceland was listed on the UN Human Development Index as the sixth most developed country in the world.

A seminar with the Danish scholar Ann-Sofie Gremaud was part of the exhibition. She has claimed that Iceland could be perceived as a crypto-colony as a means of understanding an underlying condition of Icelandic society: The centuries of Danish rule and a widespread negligence of its actual consequences - including the continuation of power structures that have favoured the few over the many - have had a lasting impact on Icelandic society. Additionally, the fixation on “norientalist” stereotypes can be viewed as a process of European-colonial reciprocal identity formation. As Hegel has explained, identity processes rely heavily on mutual confirmation: The center needs to define a periphery (an “other”) in order to define itself. Iceland has certainly played a vital role as “the other place”, where explosive natural power has been juxtaposed to the long history of European culture. Historical colonial association with the natural state has for instance led to Icelanders being perceived as more original, authentic, unspoiled or even uncivilized and barbaric. Reactions to that perception have sometimes included its rejection, whilst at others, embraced it and so been complicit in self-exoticisation.